There isn't a great deal of fury going on in this eleventh (chronologically) Richard Sharpe novel, but at this point it must have started getting difficult to come up with titles? Maybe?

At any rate, Sharpe's Fury is, well, another Sharpe novel, in which much the sort of thing that happens in other Sharpe novels, happens again. He survives the nearly fatal incompetence of yet another highly placed British officer and manages to distinguish himself in doing so. He gets suckered into a decidedly non-military assignment on which, potentially, the fate of the Peninsular War depends. He meets a pretty woman of loose morals at just the right between-lovers moment to enjoy her usually expensive favors for free. He earns grudging admiration and gratitude and makes new enemies. He ruffles allied feathers. He is Richard Sharpe in a Richard Sharpe novel.

The fun here is largely in the side plots, which in this novel take place largely in and around boats, as befits its overall setting of the Spanish city of Cadiz, one of Europe's oldest cities, almost completely surrounded by the sea, its inhabitants desperately afraid that their British allies are going to make it into another Gibraltar. Well, most of them are afraid; some of them are more concerned about fanning that fear for their own political ends, whether they be to make of Spain a throwback autocratic monarchy/theocracy or to liberate it as a republic (with or without the help of Napoleon) or to continue to enjoy its current state of near lawlessness and profit potential.

Which brings us back to the main plot, which has Henry Wellesley, brother of the Iron Duke and British envoy to Spain in his own right. Unhappily married, it is he who first and primarily enjoys the favors of this novel's token female, only to convince himself he's in love, pen her some very indiscreet letters in which he tries to show off and impress her and thereby gives the Brit-haters of Cadiz exactly the kind of ammunition they need to make Brit-haters of the whole of Cadiz.

Guess who gets to try to buy, steal or destroy those letters? Hint: one of them carries around a non-regulation sword and rose up from the ranks; another carries a seven-barreled volley gun and actually gets to use it a bit. And, you know, the rest of their friends.

But that's all just the middle third of the book, which is bookended with, what else, battles. The last third, in a bit of a departure for the Sharpe novels, is rather light on scenes that actually feature Sharpe, as even Bernard "I put my infantry bastard at Trafalgar" Cornwell had trouble working his hero into the Battle of Barrosa. Suffice it to say that while Sharpe was playing spy/thief, the rest of the British are channeling Buttercup's beloved: "We are men of action; lies do not become us."

Again, history knowledge acts as a spoiler for this stuff, so I'm proud of myself for avoiding that Wikipedia article until just now. And again, well, the Spanish do not come off so well, perhaps even worse than the last time they let their British allies down. Still, I have a new hero about whom I wish to learn more in Sir Thomas Graham. Wow, that guy.

Kate Sherrod blogs in prose! Absolutely partial opinions on films, books, television, comics and games that catch my attention. May be timely and current, may not. Ware spoilers.

Thursday, August 29, 2013

Monday, August 26, 2013

C.S. Harris' WHAT ANGELS FEAR

First off: trigger warning: this book contains lots and lots of conversations about rape and necrophilia and violence against women in general. Not for everybody; barely for me.

This is another one I poached off my mother's wish list when I got her an ebook reader for her birthday/Mother's Day. She has good taste in diversions, my mother, so when she wishes for a book it's usually something I'm gonna wind up wanting to read, too.

What Angels Fear, the first of a nine-books-and-probably-counting mystery series set during the Georgian era, is certainly diverting, especially in its choice of hero, one Sebastian St. Cyr, Viscount Devlin, whom I would describe as half Francis Crawford of Lymond, half Richard Sharpe, in that he is a larger-than-life aristocrat who is also a veteran of a particularly horrific tour of duty in the Napoleonic wars. But with, you know, all but bionic senses. Dude hears and sees really, really well, you guys.

Also much like Lymond, he spends most of his first novel working under a cloud of suspicion: a beautiful and somewhat famous young actress was found brutally raped and murdered -- or, actually, murdered then raped, as it turns out -- in a church, the corpse still in possession of one of St. Cyr's distinctive duelling pistols. Justice in pre-Regency England being what it is -- constables are paid a bonus of forty pounds for every conviction, for instance -- everyone seems to regard that coincidence as enough to convict him, and soon our man is on the run and his own only hope to clear his name and remain free.

St. Cyr's books do not look to much resemble Lymond's in any other respect, though, nor are they meant to. These look to be straight up cozy mysteries that just happen to be set in a historical setting; dynastic/political struggles are an element of the plot, but the intricacy and subtlety and dazzling erudition of a Dorothy Dunnett would be out of place here. Instead, we have the single, straightforward plot, full of action, description, and a tour of Seedy London with a street urchin named Tom as St. Cyr's and our guide. And a woman named Kat who is an actress/courtesan just like the victim was, who just happens to be St. Cyr's ex-lover and has rather a lot to do with the murder so is very torn about exactly how much she should help our hero.

What's really refreshing about this book, though, is its sort-of antagonist, the investigator officially in charge of this murder, Sir Henry Lovejoy. Where a lot of wrongly-accused-man-must-find-real-killer tales feature our innocent hero being stalked by boobs (or by outright enemies of the hero who are hell-bent on seeing him hang/fry/rot in jail), What Angels Fear features a magistrate-cum-detective who is as committed to finding the truth as is St. Cyr. Sir Henry Lovejoy is a former businessman who chose to become a magistrate to make up for his childlessness, not in the sense of filling a void in his own life, but in the sense of contributing to his society and its future. He appreciates the scientific method and strives to apply it to his own work, making him a figure who would be at home in what I still consider the greatest historical mystery novels of all, those of Caleb Carr. His side of the narrative is every bit as engaging as St. Cyr's, in its quiet and methodical way. I could have used a lot more of Sir Henry Lovejoy, really.

Without Lovejoy, this is very much a by-the-numbers mystery story, complete with sorta-exciting climax that felt like a level of Arkham Asylum, one of those where Batman has to grapple from gargoyle to gargoyle to find the right angle of attack (and now that I think of it, there's something ever so slightly Commissioner Gordon about Sir Henry Lovejoy). And the boss battle is good except, except, ah, I'm not sure how to complain about this without committing spoilers so go read the footnote if you don't care about spoilers.*

But in defense of all of this, mystery isn't really my genre. Like spy novels, mysteries are at best an occasional indulgence for me. I'll read the rest of the St. Cyr books sometime, but they're not knocking anything off the precarious top of my to-be-read pile.

Bet my mystery-loving mom is going to love this, though.

*Dude. I hate, hate, hate it when the ultimate bad guy turns out to be someone who hasn't even appeared as a character in the story. There have been oblique references to the person but he doesn't get any actual "on camera" time until the very end, when All Is Revealed. I call shenanigans. Shaggy dog shenanigans, even.

This is another one I poached off my mother's wish list when I got her an ebook reader for her birthday/Mother's Day. She has good taste in diversions, my mother, so when she wishes for a book it's usually something I'm gonna wind up wanting to read, too.

What Angels Fear, the first of a nine-books-and-probably-counting mystery series set during the Georgian era, is certainly diverting, especially in its choice of hero, one Sebastian St. Cyr, Viscount Devlin, whom I would describe as half Francis Crawford of Lymond, half Richard Sharpe, in that he is a larger-than-life aristocrat who is also a veteran of a particularly horrific tour of duty in the Napoleonic wars. But with, you know, all but bionic senses. Dude hears and sees really, really well, you guys.

Also much like Lymond, he spends most of his first novel working under a cloud of suspicion: a beautiful and somewhat famous young actress was found brutally raped and murdered -- or, actually, murdered then raped, as it turns out -- in a church, the corpse still in possession of one of St. Cyr's distinctive duelling pistols. Justice in pre-Regency England being what it is -- constables are paid a bonus of forty pounds for every conviction, for instance -- everyone seems to regard that coincidence as enough to convict him, and soon our man is on the run and his own only hope to clear his name and remain free.

St. Cyr's books do not look to much resemble Lymond's in any other respect, though, nor are they meant to. These look to be straight up cozy mysteries that just happen to be set in a historical setting; dynastic/political struggles are an element of the plot, but the intricacy and subtlety and dazzling erudition of a Dorothy Dunnett would be out of place here. Instead, we have the single, straightforward plot, full of action, description, and a tour of Seedy London with a street urchin named Tom as St. Cyr's and our guide. And a woman named Kat who is an actress/courtesan just like the victim was, who just happens to be St. Cyr's ex-lover and has rather a lot to do with the murder so is very torn about exactly how much she should help our hero.

What's really refreshing about this book, though, is its sort-of antagonist, the investigator officially in charge of this murder, Sir Henry Lovejoy. Where a lot of wrongly-accused-man-must-find-real-killer tales feature our innocent hero being stalked by boobs (or by outright enemies of the hero who are hell-bent on seeing him hang/fry/rot in jail), What Angels Fear features a magistrate-cum-detective who is as committed to finding the truth as is St. Cyr. Sir Henry Lovejoy is a former businessman who chose to become a magistrate to make up for his childlessness, not in the sense of filling a void in his own life, but in the sense of contributing to his society and its future. He appreciates the scientific method and strives to apply it to his own work, making him a figure who would be at home in what I still consider the greatest historical mystery novels of all, those of Caleb Carr. His side of the narrative is every bit as engaging as St. Cyr's, in its quiet and methodical way. I could have used a lot more of Sir Henry Lovejoy, really.

Without Lovejoy, this is very much a by-the-numbers mystery story, complete with sorta-exciting climax that felt like a level of Arkham Asylum, one of those where Batman has to grapple from gargoyle to gargoyle to find the right angle of attack (and now that I think of it, there's something ever so slightly Commissioner Gordon about Sir Henry Lovejoy). And the boss battle is good except, except, ah, I'm not sure how to complain about this without committing spoilers so go read the footnote if you don't care about spoilers.*

But in defense of all of this, mystery isn't really my genre. Like spy novels, mysteries are at best an occasional indulgence for me. I'll read the rest of the St. Cyr books sometime, but they're not knocking anything off the precarious top of my to-be-read pile.

Bet my mystery-loving mom is going to love this, though.

*Dude. I hate, hate, hate it when the ultimate bad guy turns out to be someone who hasn't even appeared as a character in the story. There have been oblique references to the person but he doesn't get any actual "on camera" time until the very end, when All Is Revealed. I call shenanigans. Shaggy dog shenanigans, even.

Sunday, August 25, 2013

Matt Wallace's THE FAILED CITIES

It can be easy to forget when reading this newly published hardcover collection of what once was a serialized podcast novel/anthology called "The Failed Cities Monologues" that it was originally penned in 2006 -- before the current financial crisis, before cities like Stockton and San Bernadino, CA and Detroit, MI went bankrupt. We were still riding relatively high, in 2006. Which is to say that Matt Wallace was maybe a little bit prescient.

The Failed Cities really concerns what was a single city bifurcated by a river -- which made it all the easier to let half of it go to crap when circumstances made its leadership give up on the poorer side of the river, withdrawing the police rather than utilities support after a rigged vote and thus letting the cheap side fall into lawlessness, a shanty town with seven story apartment buildings. The rich side, meanwhile, has its own problems, hosting, for instance, a giant crap crater that was originally a building site for what was going to be the most luxurious arcology build in the history of ever, until the financing fell through. Oops.

Within this world, eight point of view characters are living their lives: a street preacher (member of a sect of these, who have more or less taken on the role of the police in a wholly informal way), a pulp fiction writer (who makes ends meet by fighting in an arena and getting beaten to a pulp), a hot-rodder (who has a side business in acting as a one-man underground railroad for abused sex workers), a pair of brother and sister assassins (one of whom has had weird bone grafting surgery so all of her joints are essentially deadly edged weapons and the other of whom is Just. Huge.), a freelance moderator/negotiator (who got his start by talking his way out of a bar fight he kind of started), a Ukrainian immigrant escaping his family's legacy of heroism (who winds up backing into a heroic role as the Detective Who Will Catch The Serial Killer and immediately regretting it) and a black widow femme fatale (who sees through everyone else's schemes and plots to turn all those schemes on their heads). Each takes a turn at forwarding the overall narrative as their stories are intercut and overlap with one another to portray a world of lawlessness, struggle and occasional hope.

And yes, I'm going to mention the Godbody standard here, for The Failed Cities comes closest to meeting it of any book I've read, closer even than The Book of Skulls did. Which is to say that each character voice is distinct and believable, including those of the women, and I'm fairly certain a person familiar with the book could guess who was speaking from a randomly chosen passage read a loud, within a paragraph or two, if not a sentence or two. That takes talent.

So, top notch world building, top notch characterization, an interesting and intricate plot -- does this book have any flaws? Perhaps only the spidery typography, the font so thin it looks faint and was thus a little hard to read for these middle-aged eyes. But the contents thus displayed were so good -- and the hardcover containing them so gorgeous -- that I soldiered on with it. And hey, it's not like this was my first time visiting the Failed Cities; I listened to the podcast back in the day, which is why I knew I had to have this luxe edition. Go listen to the free original podcast version and see if it doesn't make you want one, too.

The Failed Cities really concerns what was a single city bifurcated by a river -- which made it all the easier to let half of it go to crap when circumstances made its leadership give up on the poorer side of the river, withdrawing the police rather than utilities support after a rigged vote and thus letting the cheap side fall into lawlessness, a shanty town with seven story apartment buildings. The rich side, meanwhile, has its own problems, hosting, for instance, a giant crap crater that was originally a building site for what was going to be the most luxurious arcology build in the history of ever, until the financing fell through. Oops.

Within this world, eight point of view characters are living their lives: a street preacher (member of a sect of these, who have more or less taken on the role of the police in a wholly informal way), a pulp fiction writer (who makes ends meet by fighting in an arena and getting beaten to a pulp), a hot-rodder (who has a side business in acting as a one-man underground railroad for abused sex workers), a pair of brother and sister assassins (one of whom has had weird bone grafting surgery so all of her joints are essentially deadly edged weapons and the other of whom is Just. Huge.), a freelance moderator/negotiator (who got his start by talking his way out of a bar fight he kind of started), a Ukrainian immigrant escaping his family's legacy of heroism (who winds up backing into a heroic role as the Detective Who Will Catch The Serial Killer and immediately regretting it) and a black widow femme fatale (who sees through everyone else's schemes and plots to turn all those schemes on their heads). Each takes a turn at forwarding the overall narrative as their stories are intercut and overlap with one another to portray a world of lawlessness, struggle and occasional hope.

And yes, I'm going to mention the Godbody standard here, for The Failed Cities comes closest to meeting it of any book I've read, closer even than The Book of Skulls did. Which is to say that each character voice is distinct and believable, including those of the women, and I'm fairly certain a person familiar with the book could guess who was speaking from a randomly chosen passage read a loud, within a paragraph or two, if not a sentence or two. That takes talent.

So, top notch world building, top notch characterization, an interesting and intricate plot -- does this book have any flaws? Perhaps only the spidery typography, the font so thin it looks faint and was thus a little hard to read for these middle-aged eyes. But the contents thus displayed were so good -- and the hardcover containing them so gorgeous -- that I soldiered on with it. And hey, it's not like this was my first time visiting the Failed Cities; I listened to the podcast back in the day, which is why I knew I had to have this luxe edition. Go listen to the free original podcast version and see if it doesn't make you want one, too.

Labels:

dystopian fiction,

Podiobooks,

Theodore Sturgeon

Thursday, August 22, 2013

Paul S. Kemp's THE HAMMER AND THE BLADE

Pulp fantasy, ahoy!

One of the downsides of partaking in a subscription service like Angry Robot's ebook one is that occasionally one winds up with a backlog, if one is, as I do, reading a lot of other stuff as well. Since this has been my Summer of Napoleonic War Fiction, I haven't read as much of the genres and genre mash-ups that are Angry Robot's specialty; I've just harvested my subscription each month and sort of gloated at the volume of most-likely-good stuff I have in store for myself.

It's pretty enjoyable. But then sometimes my feed suddenly contains a sequel, a sequel that makes me curious and I sit down to have a look at it and realize, BOOM!, it's a sequel! And I haven't read the first one yet! But now I really want to!

And that's pretty much what happened with the good old-fashioned pulp fantasy funtimes of The Hammer and the Blade, author Paul S. Kemp's first Egil and Nix adventure. Egil and Nix are old adventuring buddies who already have a long and storied history together as this novel starts; in fact, they've been adventuring together for so long that, as they finish their latest bout of tomb-raiding and realize they don't really need the loot anymore, they decide this is going to be their last raid and they're then going to head back to civilization and invest in a legitimate business. Like, say, a brothel.* Because hey, this is still fantasy, you guys.

Their ambitions get thwarted, of course, because in the course of their last tomb-raiding mission, they were pretty much forced to kill a demon (this is all just in the prologue, so I'm not really spoiling anything) that turns out to be very important to an ancient and powerful and baroquely weird family back in the city. Our duo may think they're too old for this sheet, but the Norristru clan (the Tessier-Ashpools by way of the Groans, basically) would beg to differ. And said clan are more than powerful enough to get their way, so off go Egil and Nix on yet another adventure.

As excuses for a small-scale -- the world and its fate are not at stake, just the lives of our two protagonists -- sword and sorcery tale go, well, I've encountered worse. And I got very quickly involved in rooting for this duo, whose relationship is conducted mostly through very enjoyable and snarky dialogue of that laddish kind in which 95% of the conversation is one giving the other crap for his well-known foibles, in full knowledge that at some point in time said foibles have saved both of their lives.

And foibles they most certainly have. Egil, the Hammer, is a priest -- and possibly the only worshipper, making him, as he observes, the High Priest -- of the Momentary God, very devoted to his once-divine-but-only-for-a-little-while-that-one-time deity, a wielder of wit and two great big war-hammers. Nix, the Blade, is a stealth artist and thief, with a satchel full of "gew-gaws" that sometimes help him charm or pick locks and perform other tasks and sometimes backfire in hilariously inconvenient ways They make a fine and successful team, and both are clever and witty and fun to read about.

If you're looking for equally interesting and well-rounded female characters, though, ehhh. Egil and Nix have no female counterpart, but I've learned not to expect one (unless I'm reading my good friend Jennifer Williams' work, some of which you, too, will be able to read in a few short months when her publisher [hooray!] releases it to much fanfare. Stay tuned!). There are, though, women on the bad guys' side, a mother and two sisters, members of the main baddie's family, who as the females in the clan bear the horrible, nasty brunt of said clan's pact with the devil that Egil and Nix kill in the prolog. They have powers and schemes of their own, but since their brother keeps them in a drugged sleep through most of the novel, they exist merely as victims and occasional sources of bad dreams for Nix, who finds himself torn between the spell of compulsion their brother laid on him and Egil to encourage their cooperation, which gives him great pain and sick feelings whenever he so much as thinks of rebelling, and the equally sorcery-induced urge to help the sleeping beauties on Rakon's cart. The sisters' one act of real agency, though, is a doozy, resulting nothing more and nothing less than a forced empathy, causing Egil and Nix to experience mentally the very physical horrors in store for the sisters if Rakon succeeds.

It's enough.

In addition to all the sorcery and tomb-raiding, there are some smashing set-piece battles, especially the mid-novel attack on the caravan by the demonic, reptilian Vwynn, scaly flying beasts with inch-long talons, sharp nasty pointy teeth and wings, that threaten to overwhelm our troop by sheer numbers. It's a great, exciting scene, finely balanced between chaos and detailed blow-by-blow.

All in all, this is a great bit of brain candy, full of action and humor and blood and shouty men and shiny armor. And occasional fauxnachronistic language ("incant" and "incanting" are often used, and prove to be almost as annoying to this reader as "whilst") but not so much as to be unforgiveable. Pulp fantasy, how I've missed you!

*Said brothel rejoicing in the cheerfully misogynist name of the Slick Tunnel, its cheerful misogyny emphasized for us readers by its constantly being italicized, so the female reader is slapped in the face with it each time the place is named. Did I mention that this book is a bit on the laddish side? Sigh.Still, at least nobody gets raped.

One of the downsides of partaking in a subscription service like Angry Robot's ebook one is that occasionally one winds up with a backlog, if one is, as I do, reading a lot of other stuff as well. Since this has been my Summer of Napoleonic War Fiction, I haven't read as much of the genres and genre mash-ups that are Angry Robot's specialty; I've just harvested my subscription each month and sort of gloated at the volume of most-likely-good stuff I have in store for myself.

It's pretty enjoyable. But then sometimes my feed suddenly contains a sequel, a sequel that makes me curious and I sit down to have a look at it and realize, BOOM!, it's a sequel! And I haven't read the first one yet! But now I really want to!

And that's pretty much what happened with the good old-fashioned pulp fantasy funtimes of The Hammer and the Blade, author Paul S. Kemp's first Egil and Nix adventure. Egil and Nix are old adventuring buddies who already have a long and storied history together as this novel starts; in fact, they've been adventuring together for so long that, as they finish their latest bout of tomb-raiding and realize they don't really need the loot anymore, they decide this is going to be their last raid and they're then going to head back to civilization and invest in a legitimate business. Like, say, a brothel.* Because hey, this is still fantasy, you guys.

Their ambitions get thwarted, of course, because in the course of their last tomb-raiding mission, they were pretty much forced to kill a demon (this is all just in the prologue, so I'm not really spoiling anything) that turns out to be very important to an ancient and powerful and baroquely weird family back in the city. Our duo may think they're too old for this sheet, but the Norristru clan (the Tessier-Ashpools by way of the Groans, basically) would beg to differ. And said clan are more than powerful enough to get their way, so off go Egil and Nix on yet another adventure.

As excuses for a small-scale -- the world and its fate are not at stake, just the lives of our two protagonists -- sword and sorcery tale go, well, I've encountered worse. And I got very quickly involved in rooting for this duo, whose relationship is conducted mostly through very enjoyable and snarky dialogue of that laddish kind in which 95% of the conversation is one giving the other crap for his well-known foibles, in full knowledge that at some point in time said foibles have saved both of their lives.

And foibles they most certainly have. Egil, the Hammer, is a priest -- and possibly the only worshipper, making him, as he observes, the High Priest -- of the Momentary God, very devoted to his once-divine-but-only-for-a-little-while-that-one-time deity, a wielder of wit and two great big war-hammers. Nix, the Blade, is a stealth artist and thief, with a satchel full of "gew-gaws" that sometimes help him charm or pick locks and perform other tasks and sometimes backfire in hilariously inconvenient ways They make a fine and successful team, and both are clever and witty and fun to read about.

If you're looking for equally interesting and well-rounded female characters, though, ehhh. Egil and Nix have no female counterpart, but I've learned not to expect one (unless I'm reading my good friend Jennifer Williams' work, some of which you, too, will be able to read in a few short months when her publisher [hooray!] releases it to much fanfare. Stay tuned!). There are, though, women on the bad guys' side, a mother and two sisters, members of the main baddie's family, who as the females in the clan bear the horrible, nasty brunt of said clan's pact with the devil that Egil and Nix kill in the prolog. They have powers and schemes of their own, but since their brother keeps them in a drugged sleep through most of the novel, they exist merely as victims and occasional sources of bad dreams for Nix, who finds himself torn between the spell of compulsion their brother laid on him and Egil to encourage their cooperation, which gives him great pain and sick feelings whenever he so much as thinks of rebelling, and the equally sorcery-induced urge to help the sleeping beauties on Rakon's cart. The sisters' one act of real agency, though, is a doozy, resulting nothing more and nothing less than a forced empathy, causing Egil and Nix to experience mentally the very physical horrors in store for the sisters if Rakon succeeds.

It's enough.

In addition to all the sorcery and tomb-raiding, there are some smashing set-piece battles, especially the mid-novel attack on the caravan by the demonic, reptilian Vwynn, scaly flying beasts with inch-long talons, sharp nasty pointy teeth and wings, that threaten to overwhelm our troop by sheer numbers. It's a great, exciting scene, finely balanced between chaos and detailed blow-by-blow.

All in all, this is a great bit of brain candy, full of action and humor and blood and shouty men and shiny armor. And occasional fauxnachronistic language ("incant" and "incanting" are often used, and prove to be almost as annoying to this reader as "whilst") but not so much as to be unforgiveable. Pulp fantasy, how I've missed you!

*Said brothel rejoicing in the cheerfully misogynist name of the Slick Tunnel, its cheerful misogyny emphasized for us readers by its constantly being italicized, so the female reader is slapped in the face with it each time the place is named. Did I mention that this book is a bit on the laddish side? Sigh.Still, at least nobody gets raped.

Labels:

Angry Robot Books,

fantasy fiction,

Paul S. Kemp,

pulp fantasy

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

Hugh Howey's DUST

"The idea of saving anything was folly, a life especially. No life had ever been truly saved, not in the history of mankind. They were merely prolonged. Everything comes to an end."Readers of Hugh Howey's Silo series are by now prepared for a certain degree of bleakness, but there are moments of downright agonizing despair in Dust, its final installment. Moments that made me cry out to my lodger "Who does Hugh think he is, George R. R. Effing Martin?" to which my lodger replied "No, because then you would have had to wait seven years and then you'd only have gotten half the story."

True, true.

I've taken quite a series of emotional beatings at the authorial hands of Mr. Howey as I've read these books. I've come to care deeply about their characters, especially the engineer-turned-leader Juliet and the kid who came of age to become a silo's sysop, Lukas, only to go through the wringer with them as they've weathered bout after bout of horrific social and psychological turbulence. I've come, too, to pretty much despise architect-turned-politician-turned-overlord-turned-half-assed-saboteur Donald, and to loathe his manipulator and master, Thurman. It's fun every once in a while to have clearly defined heroes and villains to cheer and to hiss at.

Which would hint that there's a certain lack of complexity at work in the Silo books, if that was all that could be said about them. But that would be a mistake, because these works are actually all about complexity, about dynamic, chaotic messiness versus imposed order, about the overthrow of a particularly odious form of generational tyranny, about individuals setting out to out-think a system minutely designed to prevent them from thinking at all, except about meeting basic survival needs and keeping running the intricate machine that lets them meet those needs in an environment for which they are evolutionarily ill-suited.

The world of the Silo series has been gradually revealed as one of layers and layers of horror and sadness, albeit one in which families and friendships and the quotidian pleasures of daily life still, in some fashion, prevail. As the Wool and Shift stories have unfolded, the nature of Silo life is revealed as even more sad and horrible than it had at first seemed: the Silos are not merely survival machines, but part of a rather twisted and terrible effort to warp all of humanity to conform to one man's imperial will, a captive breeding program of sorts, to produce perfectly obedient and docile subjects. It's generational tyranny writ large, with the added horror of the original generation still being around to inflict it from afar, enabled by super sci-fi technological advantages denied to the ordinary Silo dwellers. The generation -- the man -- that killed the world still holds the power of life and death over the people he "saved."

But even the most tightly controlled breeding program has its sports, its throwbacks, its tall poppies. Dust is a celebration of those tall poppies; even as some of them get mowed down, the rest stubbornly refuse to conform to the imperial will, to remain ignorant and powerless and acquiescent to the expectations of their masters. Juliet, Lukas and their friends, with a little help from a belatedly aware and rebellious Donald, are determined to think their way out of and around the limitations imposed on them, to turn, if necessary, their elaborate machine for survival into a machine for revenge. Or for liberation.

The tension between the will to revenge and the will to freedom is a major theme of Dust, as Juliet struggles between rage at what she has learned about the nature of her world and hope that she and hers can transcend that world. She has been given strong reasons to yield to either impulse*, and the reader is kept speculating about what she will choose for most of the novel. This tension coupled with that of Howey's vast talent for cliffhangers that are never tacked on but always naturally evolve from situations make Dust a page-turner even for the die-hard Silo fan who is devastated that it's the last of the series and doesn't want it to be over yet.

Meanwhile, Donald's story and character also develop satisfyingly. Belatedly taking on an agency that it's pretty much criminal for him to have rejected for centuries of alternating Shift work and cryosleep,** Donald finally becomes a hero of sorts, though still in a bit of a half-assed way. I will confess to rather enjoying the punishment his new agency earned him, a little. But what really saved his story was the introduction of his sister Charlotte, whom he awakens against all the rules of the master Silo, in which the crew's female family members are kept in cryosleep indefinitely so they don't cause any fights or problems. Charlotte, formerly an Air Force drone pilot, is everything that Donald is not, and it's largely through her, and the need to keep her a secret, that Donald finally gets some steel in his spine, enough to become as important to Juliet's storyline as he is to his own.

Going into Dust, I was really wondering how Howey was finally going to knit Donald's and Juliet's stories into any kind of satisfying whole, especially since he was going to have to do this within the larger framework of wrapping up the series. I'm happy to say he pulled it off splendidly, by letting his characters be who they are, think for themselves, and experience fully the consequences of their decisions (or indecision). Dust is a satisfying conclusion to a powerful and deeply moving series. One wishes Ronald D. Moore had somehow come across Mr. Howey a few years ago. Cough. Disappearing Starbuck. Cough. Howey could have finished BSG right.

He finished the Silo series right. And for that, he deserves all the applause and accolades we may give him.

*And let's just say that it's probably a good thing that she is kept ignorant of one key aspect of life in the master Silo from which Donald (and his illicitly revived sister Charlotte) surreptitiously help her, that of the situation in which members of her gender find themselves -- or would find themselves, if they were ever allowed to awaken -- for the greater good. Had Juliet ever learned of the Senators No Girls Allowed at the Top Because Breeding and Sexual Tension rule, there would have been no stopping her on the quest for revenge.

**Especially criminal since his one-time-girlfriend, the Senator's daughter Anna -- the only woman besides Charlotte to have ever been conscious in the master Silo -- pretty much had to die to finally provoke this agency.

Labels:

dystopian fiction,

favorites,

Hugh Howey,

science fiction,

Silo series

Friday, August 16, 2013

#DTTATDIWSF - aka the Definitive Top Ten All Time Desert Island Works of Speculative Fiction

Author, Parsec Award-winning podcaster, screenwriter and former professional wrestler Matt Wallace is often provocative, as a writer and as a tweeter. Today he challenged his followers to cook up their own personal "Definitive Top Ten All Time Desert Island Works of Speculative Fiction" list, as an exercise in figuring out what we most appreciate in the genre. Matt's own list is right here, but since Tumblr is blocked at work I haven't been able to peek at it as of this writing.

I've been ruminating on this for quite a while now, and below is what I've come up with. Note these are in no particular order except in which I thought of them -- which is probably meaningful enough, right there.

1. Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle. For me this is a desert island book by any definition you care to name. It would even be on my list if that list were merely of objects of any kind. Fire starter, soap, water bottle, knife, Man in the High Castle. I do not exaggerate. Something to occupy the mind is as vital as being able to catch and kill and cook and eat, and this book has everything I look for in a good read: provocative ideas (like an alternate history in which the Axis won WWII and Germany and Japan divided up North America between them), delicate passages of philosophical speculation, sensitive characterizations and a weird plot that feels a little different every time I read it. Dick always claimed that the I Ching wrote this novel and he's just the dude that cast the yarrow stalks. Whether you believe in that stuff or not, the result is unlike anything you'll ever read.

2. John Brunner's The Sheep Look Up. Self-denying prophecy you should thank whatever you believe in didn't come true, combined with a fascinating series of intertwined plots. Because Desert Island reading shouldn't always be comfort reading. Click on the linked title for my original blog post on it. I've only read it once, but I know I'll be returning to it again and again. I'm a bit of a masochist that way.

3. Tim Powers' Last Call. Really, it's a toss-up for me between this one and The Anubis Gates, but I knew that one of them had to be on this list. This is another book that ticks every box for me, in which the archetypes of the Tarot meet the warty fat man in the famous Mandelbrot fractal and Bugsy Siegel was once the Fisher King of the American West. I could almost recite it by heart, but I have yet to tire of it, and I've read it probably even more times than I've read The Man in the High Castle (but only because I got my hands on this one first).

4. Theodore Sturgeon's Godbody. Far more than simply a parable-with-Jesus-figure, Theodore Sturgeon's last (and best) novel is just good medicine. It might be argued that this is literary, rather than speculative fiction; its miracles are of understanding and of the power of fellowship and love (brotherly more than romantic), its technical achievement -- each chapter is written by a different character, in the first person, and Sturgeon gives each narrator such a distinctive voice that fellow spec fic master Robert A. Heinlein famously observed that if you had someone pick a page at random and read it aloud to you, you could tell instantly which character was speaking within just a line or two -- one I wish were more widely known and appreciated by the mainstream. This is the book I turn to when despair or serious biting misanthropy threaten to overtake me. I'm always the better for enjoying it again.

5. Harlan Ellilson's Angry Candy. Many might argue that Unca Harlan has produced better short story collections, or at least more famous ones, but this one holds the most deeply felt and personal significance for me. Each story -- and its howlingly bitter and painful-to-read preface by the author -- is a reaction to the grim realities of death and loss. Sometimes it treats of the grieving process, or what happens when you get stuck in it, as does "The Function of Dream Sleep" (the single most important short story in my world). Others speculate on what might be done with one last hour of time that's been knocked loose in the universe -- who wouldn't want to grab it for him or herself to spend with a lost loved one? -- and "The Paladin of the Lost Hour"'s role in protecting it from abuse. Then there's "Eidolons", telling a bizarre story in a series of searingly wonderful aphorisms and passages like this one:

6. Walter Moers' Rumo & His Miraculous Adventures. OK, this is another toss-up. I might actually love A Wild Ride Through the Night a bit more, but this is a Zamonia book, and furthermore the first one of those I got to read, and so holds a special place in my sentimental little heart. Plus, I'm a dog person, and how can one not love a Wolpertig? Which is, of course, a sentient, superintelligent, superbrave antlered dog? Who also inhabits a world of sentient shark grubs and highly literary dinosaurs and puns in every language and talking swords... yes, talking swords! Rumo himself has one named Dandelion. Moers is one of the most delightful writers ever to have existed and this is for sure his most delightful book. If it does not charm you, you have neither a brain nor a heart and how is it you're even reading this blog?

7. Jorge Luis Borges' Labyrinths. My first and still my favorite Borges collection, at least that could by any stretch be included as speculative fiction (his poetry collection The Gold of the Tigers would bump it a bit on a more general books list). This is a bit of a sneaky choice on my part since it includes some of Borges' essays as well, but hey, it also has most of his greatest thought-experiment-cum-short-stories, in which his characters rewrite Don Quixote word for word from scratch and thereby produce a "richer" version of the original, dream up a whole 'nother human being fiber by fiber and actually creates that being, and a condemned man makes his last minute of life stretch into infinity. To name just a few. Borges inspired pretty much everyone else in the genre whom I respect; he still blows me away to this day.

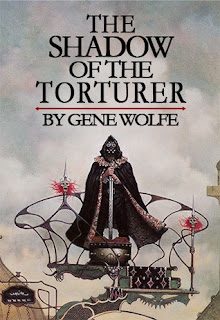

8. Gene Wolfe's Book of the New Sun. All twelve volumes of it. Yes, this is totally cheating. What are you going to do about it. I'm not afraid of you? Well, I might be afraid of you if you're Matt Wallace, but actually I had a drink with him once and found him very pleasant company, so there. Anyway, Wolfe's tightly written yet sprawling, maddeningly obtuse is-this-the-past-or-the-future-or-the-present-or-all-of-it science fiction/fantasy hybrid about an ordinary guy (who might be a god but then again might just be some schmo) who somehow winds up tasked with traveling across time and space to find the McGuffin That Will Reignite the Sun (and who also may or not be 1. Along for the ride on a generational spaceship in the form of a hollowed-out comet and 2. Living amongst the weird inhabitants of the dual planetary system to which that ship travels, which system might just actually be Earth/Urth depending on which theory) will no doubt keep me scratching my head and dropping my jaw for the rest of my life. I develop a different theory about what's going on every single time. And I promise I'll get back to the Suns Suns Suns post series soon. Because there is SO MUCH MORE I want to say about these books. Oh, and the above cover to the very first book, Shadow of the Torturer, is one of my favorite book covers of all time.

9. Clark Thomas Carlton's Prophets of the Ghost Ants. Is this one of the greatest works of speculative fiction of all time? Probably not. But this is my list, and of all the books I've ever read, this one feels the most like it was written just for me, and I love it. It's got insects galore (a key to my happiness, six-legged arthopods), a well-done, an admittedly kind of standard fantasy plot but with peculiar Dune-like grace notes that are all about individual vs collective choices and question very strongly the role of religion and received belief in any life that could remotely be called human ,well-realized and imaginative world-building, and did I mention insects? Ants, roaches, wasps, more ants, termites, beetles... you get the idea. True, I might get sick of it if I'm stuck on that desert island for decades, but you know that by then I'll be writing Antasy fan fiction on palm leaves in my own blood by then anyway.

10. Alastair Reynold's Century Rain. Reynolds is my favorite living science fiction author, as I have said many times on his blog. When it comes to one of his books, it's not a question of love or merely like (let alone dislike), but only of how intensely do I love. This story of a future archaeologist who has built a career on investigating the aftermath of a nanotech disaster that made Earth uninhabitable, and the weird planet-sized diorama of mid 20th century Earth that is discovered at the end of a wormhole in space is loaded with gorgeous details, eerie speculation, cosmic awe, factional tension and just plain awesomeness. I would prefer to just get to take all of my Reynolds with me, but if I had to pick just one, it would be this. Just because it's so pretty and jazzy and lovely and cool.

Honorable mentions, just because: Frank Herbert's Dune, Bruce Sterling's Distraction, Ken MacLeod's The Star Fraction, Hugh Howey's Wool Omnibus and Ramez Naam's Nexus.

I've been ruminating on this for quite a while now, and below is what I've come up with. Note these are in no particular order except in which I thought of them -- which is probably meaningful enough, right there.

1. Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle. For me this is a desert island book by any definition you care to name. It would even be on my list if that list were merely of objects of any kind. Fire starter, soap, water bottle, knife, Man in the High Castle. I do not exaggerate. Something to occupy the mind is as vital as being able to catch and kill and cook and eat, and this book has everything I look for in a good read: provocative ideas (like an alternate history in which the Axis won WWII and Germany and Japan divided up North America between them), delicate passages of philosophical speculation, sensitive characterizations and a weird plot that feels a little different every time I read it. Dick always claimed that the I Ching wrote this novel and he's just the dude that cast the yarrow stalks. Whether you believe in that stuff or not, the result is unlike anything you'll ever read.

2. John Brunner's The Sheep Look Up. Self-denying prophecy you should thank whatever you believe in didn't come true, combined with a fascinating series of intertwined plots. Because Desert Island reading shouldn't always be comfort reading. Click on the linked title for my original blog post on it. I've only read it once, but I know I'll be returning to it again and again. I'm a bit of a masochist that way.

3. Tim Powers' Last Call. Really, it's a toss-up for me between this one and The Anubis Gates, but I knew that one of them had to be on this list. This is another book that ticks every box for me, in which the archetypes of the Tarot meet the warty fat man in the famous Mandelbrot fractal and Bugsy Siegel was once the Fisher King of the American West. I could almost recite it by heart, but I have yet to tire of it, and I've read it probably even more times than I've read The Man in the High Castle (but only because I got my hands on this one first).

4. Theodore Sturgeon's Godbody. Far more than simply a parable-with-Jesus-figure, Theodore Sturgeon's last (and best) novel is just good medicine. It might be argued that this is literary, rather than speculative fiction; its miracles are of understanding and of the power of fellowship and love (brotherly more than romantic), its technical achievement -- each chapter is written by a different character, in the first person, and Sturgeon gives each narrator such a distinctive voice that fellow spec fic master Robert A. Heinlein famously observed that if you had someone pick a page at random and read it aloud to you, you could tell instantly which character was speaking within just a line or two -- one I wish were more widely known and appreciated by the mainstream. This is the book I turn to when despair or serious biting misanthropy threaten to overtake me. I'm always the better for enjoying it again.

5. Harlan Ellilson's Angry Candy. Many might argue that Unca Harlan has produced better short story collections, or at least more famous ones, but this one holds the most deeply felt and personal significance for me. Each story -- and its howlingly bitter and painful-to-read preface by the author -- is a reaction to the grim realities of death and loss. Sometimes it treats of the grieving process, or what happens when you get stuck in it, as does "The Function of Dream Sleep" (the single most important short story in my world). Others speculate on what might be done with one last hour of time that's been knocked loose in the universe -- who wouldn't want to grab it for him or herself to spend with a lost loved one? -- and "The Paladin of the Lost Hour"'s role in protecting it from abuse. Then there's "Eidolons", telling a bizarre story in a series of searingly wonderful aphorisms and passages like this one:

Did you have one of those days today, like a nail in the foot? Did the pterodactyl corpse dropped by the ghost of your mother from the spectral Hindenburg forever circling the Earth come smashing through the lid of your glass coffin? Did the New York strip steak you attacked at dinner suddenly show a mouth filled with needle-sharp teeth, and did it snap off the end of your fork, the last solid-gold fork from the set Anastasia pressed into your hands as they took her away to be shot? Is the slab under your apartment building moaning that it cannot stand the weight on its back a moment longer, and is the building stretching and creaking? Did a good friend betray you today, or did that good friend merely keep silent and fail to come to your aid? Are you holding the razor at your throat this very instant? Take heart, comfort is at hand. This is the hour that stretches. Djam karet. We are the cavalry. We're here. Put away the pills. We'll get you through this bloody night. Next time, it'll be your turn to help us.

7. Jorge Luis Borges' Labyrinths. My first and still my favorite Borges collection, at least that could by any stretch be included as speculative fiction (his poetry collection The Gold of the Tigers would bump it a bit on a more general books list). This is a bit of a sneaky choice on my part since it includes some of Borges' essays as well, but hey, it also has most of his greatest thought-experiment-cum-short-stories, in which his characters rewrite Don Quixote word for word from scratch and thereby produce a "richer" version of the original, dream up a whole 'nother human being fiber by fiber and actually creates that being, and a condemned man makes his last minute of life stretch into infinity. To name just a few. Borges inspired pretty much everyone else in the genre whom I respect; he still blows me away to this day.

8. Gene Wolfe's Book of the New Sun. All twelve volumes of it. Yes, this is totally cheating. What are you going to do about it. I'm not afraid of you? Well, I might be afraid of you if you're Matt Wallace, but actually I had a drink with him once and found him very pleasant company, so there. Anyway, Wolfe's tightly written yet sprawling, maddeningly obtuse is-this-the-past-or-the-future-or-the-present-or-all-of-it science fiction/fantasy hybrid about an ordinary guy (who might be a god but then again might just be some schmo) who somehow winds up tasked with traveling across time and space to find the McGuffin That Will Reignite the Sun (and who also may or not be 1. Along for the ride on a generational spaceship in the form of a hollowed-out comet and 2. Living amongst the weird inhabitants of the dual planetary system to which that ship travels, which system might just actually be Earth/Urth depending on which theory) will no doubt keep me scratching my head and dropping my jaw for the rest of my life. I develop a different theory about what's going on every single time. And I promise I'll get back to the Suns Suns Suns post series soon. Because there is SO MUCH MORE I want to say about these books. Oh, and the above cover to the very first book, Shadow of the Torturer, is one of my favorite book covers of all time.

9. Clark Thomas Carlton's Prophets of the Ghost Ants. Is this one of the greatest works of speculative fiction of all time? Probably not. But this is my list, and of all the books I've ever read, this one feels the most like it was written just for me, and I love it. It's got insects galore (a key to my happiness, six-legged arthopods), a well-done, an admittedly kind of standard fantasy plot but with peculiar Dune-like grace notes that are all about individual vs collective choices and question very strongly the role of religion and received belief in any life that could remotely be called human ,well-realized and imaginative world-building, and did I mention insects? Ants, roaches, wasps, more ants, termites, beetles... you get the idea. True, I might get sick of it if I'm stuck on that desert island for decades, but you know that by then I'll be writing Antasy fan fiction on palm leaves in my own blood by then anyway.

10. Alastair Reynold's Century Rain. Reynolds is my favorite living science fiction author, as I have said many times on his blog. When it comes to one of his books, it's not a question of love or merely like (let alone dislike), but only of how intensely do I love. This story of a future archaeologist who has built a career on investigating the aftermath of a nanotech disaster that made Earth uninhabitable, and the weird planet-sized diorama of mid 20th century Earth that is discovered at the end of a wormhole in space is loaded with gorgeous details, eerie speculation, cosmic awe, factional tension and just plain awesomeness. I would prefer to just get to take all of my Reynolds with me, but if I had to pick just one, it would be this. Just because it's so pretty and jazzy and lovely and cool.

Honorable mentions, just because: Frank Herbert's Dune, Bruce Sterling's Distraction, Ken MacLeod's The Star Fraction, Hugh Howey's Wool Omnibus and Ramez Naam's Nexus.

Labels:

fantasy fiction,

favorites,

friendship,

memes,

science fiction,

the internet

Thursday, August 15, 2013

John Fowles' THE COLLECTOR

People who know me and my love for insects might be a bit surprised to learn that I really don't approve of, and don't understand, the mania for collecting them. I had to for an assignment once in college -- for a whole semester, I was out there with a killing jar and a set of pins and all the other accoutrements. I was going to be graded on my collection, on its variety and the quality of its specimens and all the rest. As excuses for being outdoors when everybody else was (supposed to be) studying in the library or whatever, it was all right.

But I would have rather been given a quality camera and a notebook to scribble down observations about how the insects behaved while they were, you know, still alive.

The male protagonist, Frederick "Call me Ferdinand" Clegg, in John Fowles' astonishingly creepy The Collector feels differently about things. To see a rare or unusual butterfly -- he only collects butterflies, though he thinks of going into moths -- is to want it dead and pinned in a box. And since he's a very socially maladjusted man, as certainly all insect fanciers are*, he takes the same attitude towards certain specimens of other species as well. Such as lovely (human) art student Miranda, whom he encounters in one of those unfortunately magical moments in which a young man is prone to mistake an anima projection for true love, right around the time he also happens to win the football pool at work, meaning he has stumbled into the mid-century equivalent of Eff You Money.

To his credit (I guess) he decides that this specimen is better enjoyed alive, the better to someday live out his fantasy that she is going to, I guess, succumb to Stockholm Syndrome** and fall in love with him and marry him and have his babies. So he takes most of his pool winnings and buys and furnishes a human-sized terrarium for her, in the cellar of a secluded country cottage. As one does.

The fascinating thing through these early chapters is watching our man engage in some serious mental gymnastics: he's not really going to do this thing, but what if he did? He pretends to himself that he's treating it all as an elaborate thought experiment and is thus astonished, in a way that we readers are not, to find himself actually doing the things he's thought of. Buying the house. Fixing up the cellar. Stalking the girl. Carrying a cloth soaked in chloroform in his coat pocket.

This would all be very interesting reading right there -- watching a still-pretty-ordinary-despite-his-peculiarities-guy fighting this impulse he's had. But Fowles takes us from thought to deed, and just as we're thoroughly squicked out and sick of this character, Fowles seems to agree and flips the perspective; the second half of the novel is told from the perspective of Miranda, the collected, the victim.

And that's the other fascinating thing in this book, because we learn, long before Miranda becomes the author of chapters of The Collector, that while Clegg may think he's captured a pretty, helpless butterfly, he's really captured something much more powerful. Some kind of bee, maybe; Miranda has a sting. Miranda is smart and self-possessed and has a highly developed emotional intelligence that leaves Clegg floundering from their first face-to-face onwards. Not one scene between them goes according to Clegg's script; its only his extraordinary grip on his delusion, or his delusion's grip on him, that defends him from her deft emotional manipulations.

Unfortunately, that's all either of these characters turn out to be: fascinating, Clegg in his maladjusted inability to resist his icky and absurd impulses, Miranda in her repulsive fixation on class and on her idea of herself as one of the few rare and talented special ones who must battle against the ugly ordinary people. She's a mid-century epitome of the know-it-all feel-it-all fix-it-all College Girl Who Is So Much Better Than You. Though her fate is horrifying, the reader (at least this reader, who may have personality problems of her very own, oh yes) winds up kind of relishing watching her endure it, a little bit.

Which means that Fowles is a genius at eliciting reader complicity in the horrors he is depicting. This one goes on the strongly-disliked-but-undeniably-admired shelf next to Robert Silverberg's Book of Skulls. It wasn't quite the hate read that Book of Skulls was, but it certainly was not a pleasure read, either.

But it sure is remarkable.

*Sideshow Bob Grumble.

**Though that phenomenon and its terminology were not described until ten years after The Collector was first published.

But I would have rather been given a quality camera and a notebook to scribble down observations about how the insects behaved while they were, you know, still alive.

The male protagonist, Frederick "Call me Ferdinand" Clegg, in John Fowles' astonishingly creepy The Collector feels differently about things. To see a rare or unusual butterfly -- he only collects butterflies, though he thinks of going into moths -- is to want it dead and pinned in a box. And since he's a very socially maladjusted man, as certainly all insect fanciers are*, he takes the same attitude towards certain specimens of other species as well. Such as lovely (human) art student Miranda, whom he encounters in one of those unfortunately magical moments in which a young man is prone to mistake an anima projection for true love, right around the time he also happens to win the football pool at work, meaning he has stumbled into the mid-century equivalent of Eff You Money.

To his credit (I guess) he decides that this specimen is better enjoyed alive, the better to someday live out his fantasy that she is going to, I guess, succumb to Stockholm Syndrome** and fall in love with him and marry him and have his babies. So he takes most of his pool winnings and buys and furnishes a human-sized terrarium for her, in the cellar of a secluded country cottage. As one does.

The fascinating thing through these early chapters is watching our man engage in some serious mental gymnastics: he's not really going to do this thing, but what if he did? He pretends to himself that he's treating it all as an elaborate thought experiment and is thus astonished, in a way that we readers are not, to find himself actually doing the things he's thought of. Buying the house. Fixing up the cellar. Stalking the girl. Carrying a cloth soaked in chloroform in his coat pocket.

This would all be very interesting reading right there -- watching a still-pretty-ordinary-despite-his-peculiarities-guy fighting this impulse he's had. But Fowles takes us from thought to deed, and just as we're thoroughly squicked out and sick of this character, Fowles seems to agree and flips the perspective; the second half of the novel is told from the perspective of Miranda, the collected, the victim.

And that's the other fascinating thing in this book, because we learn, long before Miranda becomes the author of chapters of The Collector, that while Clegg may think he's captured a pretty, helpless butterfly, he's really captured something much more powerful. Some kind of bee, maybe; Miranda has a sting. Miranda is smart and self-possessed and has a highly developed emotional intelligence that leaves Clegg floundering from their first face-to-face onwards. Not one scene between them goes according to Clegg's script; its only his extraordinary grip on his delusion, or his delusion's grip on him, that defends him from her deft emotional manipulations.

Unfortunately, that's all either of these characters turn out to be: fascinating, Clegg in his maladjusted inability to resist his icky and absurd impulses, Miranda in her repulsive fixation on class and on her idea of herself as one of the few rare and talented special ones who must battle against the ugly ordinary people. She's a mid-century epitome of the know-it-all feel-it-all fix-it-all College Girl Who Is So Much Better Than You. Though her fate is horrifying, the reader (at least this reader, who may have personality problems of her very own, oh yes) winds up kind of relishing watching her endure it, a little bit.

Which means that Fowles is a genius at eliciting reader complicity in the horrors he is depicting. This one goes on the strongly-disliked-but-undeniably-admired shelf next to Robert Silverberg's Book of Skulls. It wasn't quite the hate read that Book of Skulls was, but it certainly was not a pleasure read, either.

But it sure is remarkable.

*Sideshow Bob Grumble.

**Though that phenomenon and its terminology were not described until ten years after The Collector was first published.

Labels:

20th century literature,

creepers,

crime fiction,

insects,

literary fiction,

Open Library finds

Monday, August 5, 2013

Philip K. Dick's IN MILTON LUMKY TERRITORY

So it might surprise folks that In Milton Lumky Territory, a very posthumously published piece of Philip K. Dick's literary fiction, is in many ways the strangest and most uncanny of his works I've ever read. Then again it might not; it's still Philip K. Dick, after all.

What makes it uncanny is the veneer of surreality -- if not unreality -- that the years have lain over its basic story of three characters whose neuroses get in the way of communicating, who are so worried about how they're coming across that they're not coming through. But it's not the characters or their strained, pained interactions (which are as beautifully and compellingly rendered as anything in highbrow White Male Narcissist literature) that make reading this novel so weird.

Its their world. Banal, ordinary, mundane, but also, through the action of time and economic upheaval, harder to believe could have ever been real than any Martian colony or post-apocalyptic California or urban techno-dystopia or tank full of humanoids engineered for another planet that Dick concocted.

In Milton Lumky Territory depicts an insignificant backwater in mid-century America, but its an America with a functioning manufacturing economy, in which it's quite possible for ordinary schmoes like PKD's typical barely competent boob-heroes to make a living, own a house, start or acquire a business, travel great distances by car just on the off-chance of maybe finding a warehouse full of newly-imported, as yet unknown and unmarketed Japanese typewriters* that can be bought cheap and sold in their downtown stores in places like Boise, Idaho not just for a profit but for enough to live on comfortably.

Fascinatingly and probably unintentionally also, In Milton Lumky Territory depicts the seeds of this economy's doom. One of the main characters, Bruce, starts off the novel working as a buyer for one of those newfangled discount houses, the ancestors to today's big box stores, before meeting Susan and letting himself be suckered into her dream of making something of her little two-bit typing and mimeographing business. There's also the aforementioned Japanese import typewriters Bruce is hankering to find and sell, the first wave of globalization and the downfall of an economy in which American businesses build durable and useful goods to be sold, used and repaired and used again in America.

It feels almost like PKD is taunting us, we who live in what can be argued is one version or another of his post-apocalyptic techno-dystopias he later created when he gave up on being a highbrow literary novelist and turned to science fiction and pulp to make his living. If only we'd been satisfied with what we had back then, maybe we wouldn't be in the mess we're in now. We could have lived in this novel, but instead, we had to break things and ruin things, let in globalization and inflation and deregulation and union-busting and general plutocracy.

But all this is just rich modern subtext to the experience of reading In Milton Lumky Territory. There is also the actual story, a soap opera plot in which Bruce and Susan meet (again**) and sort of back into deciding they're in love and should marry their fortunes together and encounter the title character, Milton Lumky, who is a traveling typewriter and typing supplies salesman (that there could be such a profession!), only to alienate him and then belatedly find they need him, for he perhaps holds the secret to finding the golden opportunity of Bruce's theoretical warehouse full of languishing game-changing Japanese machines. The characters' interactions bristle with tension, with misunderstanding, with neuroses, with the drama of miscommunication and buried intentions and revelations that seem more than a little creepy.

Which is to say that so many of the things we read PKD for are here, one does not miss the spaceships or the aliens or the revelation that the president is a robot.

I know this world existed once. My parents have vivid memories of it and I trust their accounts. Its relics can still be found all around us (myself, I have three wonderful old manual typewriters, one from 1926, that all still work beautifully because they've been lovingly cared for and used well and kindly over the years by people who respected them and expected them to last). Those empty storefronts in your city's downtown used to be occupied by businesses like Susan's; those factory buildings weren't always chic yuppie loft condos.

It's a lost world, and it's our own decisions, not a comet from space or a machine uprising or a nuclear misunderstanding that lost it for us. And that makes this the most poignant PKD of all.

*Dude. Typewriter fetishists take note. This story is about people who buy and sell and repair typewriters and paper and ribbons and carbons, and they talk about them a lot. It's pretty much heaven.

**Their original meeting lends all this a soap opera sudsiness that is good for too many guffaws to spoil here.

What makes it uncanny is the veneer of surreality -- if not unreality -- that the years have lain over its basic story of three characters whose neuroses get in the way of communicating, who are so worried about how they're coming across that they're not coming through. But it's not the characters or their strained, pained interactions (which are as beautifully and compellingly rendered as anything in highbrow White Male Narcissist literature) that make reading this novel so weird.

Its their world. Banal, ordinary, mundane, but also, through the action of time and economic upheaval, harder to believe could have ever been real than any Martian colony or post-apocalyptic California or urban techno-dystopia or tank full of humanoids engineered for another planet that Dick concocted.

In Milton Lumky Territory depicts an insignificant backwater in mid-century America, but its an America with a functioning manufacturing economy, in which it's quite possible for ordinary schmoes like PKD's typical barely competent boob-heroes to make a living, own a house, start or acquire a business, travel great distances by car just on the off-chance of maybe finding a warehouse full of newly-imported, as yet unknown and unmarketed Japanese typewriters* that can be bought cheap and sold in their downtown stores in places like Boise, Idaho not just for a profit but for enough to live on comfortably.

Fascinatingly and probably unintentionally also, In Milton Lumky Territory depicts the seeds of this economy's doom. One of the main characters, Bruce, starts off the novel working as a buyer for one of those newfangled discount houses, the ancestors to today's big box stores, before meeting Susan and letting himself be suckered into her dream of making something of her little two-bit typing and mimeographing business. There's also the aforementioned Japanese import typewriters Bruce is hankering to find and sell, the first wave of globalization and the downfall of an economy in which American businesses build durable and useful goods to be sold, used and repaired and used again in America.

It feels almost like PKD is taunting us, we who live in what can be argued is one version or another of his post-apocalyptic techno-dystopias he later created when he gave up on being a highbrow literary novelist and turned to science fiction and pulp to make his living. If only we'd been satisfied with what we had back then, maybe we wouldn't be in the mess we're in now. We could have lived in this novel, but instead, we had to break things and ruin things, let in globalization and inflation and deregulation and union-busting and general plutocracy.

But all this is just rich modern subtext to the experience of reading In Milton Lumky Territory. There is also the actual story, a soap opera plot in which Bruce and Susan meet (again**) and sort of back into deciding they're in love and should marry their fortunes together and encounter the title character, Milton Lumky, who is a traveling typewriter and typing supplies salesman (that there could be such a profession!), only to alienate him and then belatedly find they need him, for he perhaps holds the secret to finding the golden opportunity of Bruce's theoretical warehouse full of languishing game-changing Japanese machines. The characters' interactions bristle with tension, with misunderstanding, with neuroses, with the drama of miscommunication and buried intentions and revelations that seem more than a little creepy.

Which is to say that so many of the things we read PKD for are here, one does not miss the spaceships or the aliens or the revelation that the president is a robot.

I know this world existed once. My parents have vivid memories of it and I trust their accounts. Its relics can still be found all around us (myself, I have three wonderful old manual typewriters, one from 1926, that all still work beautifully because they've been lovingly cared for and used well and kindly over the years by people who respected them and expected them to last). Those empty storefronts in your city's downtown used to be occupied by businesses like Susan's; those factory buildings weren't always chic yuppie loft condos.

It's a lost world, and it's our own decisions, not a comet from space or a machine uprising or a nuclear misunderstanding that lost it for us. And that makes this the most poignant PKD of all.

*Dude. Typewriter fetishists take note. This story is about people who buy and sell and repair typewriters and paper and ribbons and carbons, and they talk about them a lot. It's pretty much heaven.

**Their original meeting lends all this a soap opera sudsiness that is good for too many guffaws to spoil here.

Saturday, August 3, 2013

Chris F. Holm's THE BIG REAP

Stop me if you've heard this one. Boy gets job. Boy hates job but is totally, totally trapped in it so he does the best he can at it according to his lights. Boy's boss gives him an important new project that's finally going to put his talents to use. Boy finds out that this only makes his job suck more. Once again, there is no girl, nor is there a spoon. Well, there is a woman (we do like being called women when we reach adulthood)* but she's pretty much off limits, because she's the boss.

I'm pretty sure we can all relate to this one.

The Big Reap is the latest in Chris F. Holm's Collector series, and a book I've been eagerly anticipating. I enjoyed the first two so very, very much. But since one of the big questions I had going into it was, could it possibly be as awesome as was The Wrong Goodbye?** That's always a dangerous question to be asking as one begins a book, and I dislike having such questions on my mind as it's a strong indicator that I'm not going to be enjoying the book solely on its own merits (see also my experience with Doctor Who: Harvest of Time, the other book I was dying to get my hands on this summer).

But really, The Wrong Goodbye was one of my favorite things I read last year. And here we are, returning to the weird, sad, funny, outrageous world of Sam Thornton once again, so how can I not compare? How can my expectations not be high?

This is not to say that they weren't met, or more precisely not met at all. But there was something missing this time around, for me, and I'm not just talking about hospital/morgue hijinks as Sam steals his next body to inhabit.*** I've been having trouble putting my finger what it is that's felt missing, though.

Partly, I suppose, it's that each successive novel has almost felt like it was playing for more modest stakes than the last. In Dead Harvest, Sam was only focusing on saving one girl, but in saving that girl he was also saving the world from an all-out war between Heaven and Hell; in The Wrong Goodbye he was trying to collect a particularly nasty soul, the possession of which might give one side an undue advantage over the other; in The Big Reap he's really just kind of acting as a janitor or errand boy. He's taking on, in the process, some seriously grotesque and powerful monsters, monsters that turn out to have had an undue influence over human history, but even after Holm brings back a few much-loved characters from the prior two books to help out (and be put in danger), Sam's jeopardy now feels like Doctor Who jeopardy, except for one thing that I can't talk about without spoiling everything.

The book is still, though, a fine, fine addition to a series that I enjoy a lot -- it made me want to re-read its predecessors, the better to admire how he's constructed the story arc (and believe me, it's worth admiring) -- but I'm not sure, if I hadn't read those books, if this book would have made me want to. As part of the series, it's still pretty satisfying, but as a stand-alone work, less so.

I still, make no mistake, read the whole thing in as few sittings as I could manage, with no flitting to other books like I do. And doubtless this will always be my way, with Mr. Holm.

For Holm has carefully left room for more Collector books to happen, and I'll be along the ride if/when he does -- I'm especially interested to see what Sam's stories are like without [REDACTED] -- but I hope he starts thinking a little bigger for them again.

Or more intimate. Because on the whole, I prefer smaller and more intimate stories. If your theme is eternal cosmic conflict, though....? Holm balanced this beautifully in the first two books. Here, he just went for a video game-style quest narrative with flashbacks. But you know what? Holy crap, do I want to play this as a video game now.

Which probably says more about me than about the book.

I still very strongly suspect that Mr. Holm is only going to get better, though.

*Well, except when "woman" is used in place of our proper names. That's a bit crass.

**Yes, his titles are all riffs on famous crime novel titles. I love this about Holm.

***For those of you who haven't read my prior reviews or the books, Sam is a sort of ghost, whose job is to collect the souls of the damned, and he has to borrow bodies from the living or the freshly dead to do it. In the first two novels, he stuck to newly dead ones for ethical reasons -- crowding a living mind and soul out of the driver's seat of its own body is kind of a dick move, yo -- but in this novel, for a variety of perfectly justifiable reasons, he's mostly piloting living bodies. A bit of tasty conscience wrestling thus occurs, but not that much, because its one of this world's conceits that every time Sam possesses a body, he leaves a little of his humanity behind when he leaves the vessel, and he's been doing this for something like 60 years as most of this story takes place.

I'm pretty sure we can all relate to this one.